Musings on children's literature, publishing, art (especially illustration), sometimes film and occasionally a few tidbits on education, especially the homeschool variety.

Thursday, June 6, 2013

Differentiating Tween and YA Books

I've been away for a while and will be light on blogging this summer due to schoolwork and my internship at my local library. I sent out a message on twitter asking if anyone might have ideas on how to differentiate "tween" and "YA" fiction. Are there certain things that you look for? Is there anything that lets you know right away? Also why do you think this distinction has become harder to manage, what's making it a gray area?

If anyone has any ideas to share, please leave comments below! I figured I'd write up a quick post so that anyone on twitter could leave a comment if desired instead of trying to fit it into a 117 character box!

Thanks!

Thursday, May 16, 2013

The Invisibility of Religion in Children's & YA Fiction

Now I’m going to preface this post with, I could very well

be wrong. And if I am, please,

please give me examples in the comments, because I’m genuinely interested in

this topic and it relates tangentially to my research.

So, why is it that religion is practically invisible in

children’s and YA literature? You

have to look far and between to find any mention not only of God or a church,

but especially of a character holding any religious beliefs or partaking in any

religious practices. Over the past

year or so, the only religious details I’ve gotten from any children’s or YA

books, that I can recall, have been Laura Amy Schlitz’s Splendors and Glooms and Ruta Sepetys’ Out of the Easy.

Now

both of these are set in the past, and it is a fact that people in general were

more religious in the past. But

I’ve read many a historical fiction book where the author failed to add the

historical detail to have their characters exhibit any religiosity. So I commend both Sepetys and Schlitz

on staying true to the historicity of their pieces and not taking out the

religious details for the sake of safeness or political correctness!

However, have you read any books recently, picture books,

children’s novels, or YA stories, especially in a contemporary setting in which

religion plays either a prominent role or at least is a part of a character’s

lifestyle or worldview in any way?

And I’m specifically referring to mainstream publishers, obviously there

are many Christian publishers for example that are heavy with these themes, but

I’m curious about major publishing houses.

You could tell me, well why don’t you just read Christian

fiction? I could, but I’m curious why religion evades so much of mainstream

children’s/YA fiction. We live in

a time when we are asking our children to relate to others, to read about

characters who live very different lives from us, and also about characters who

may resemble us or people we know but we ask readers to look at them with new

eyes. I don’t have to go to a

specialty bookstore or specially labeled off shelf in a bookstore in order to

read children’s and YA books on Asian Americans or African Americans or LGBT

characters or Latinos. We are

asking our children to embrace diversity, to read about characters from all of

these backgrounds, lifestyles etc, but why is it that we aren’t asking them to

read about characters who have religion as a major part of their life?

In part I think so many are afraid that, well if we have

them read about a character who has religion at the center of their life, or

who participates at some level in religious practices, we’ll be imposing views. Why is this? We don’t call it an

imposition when children are asked to or choose to read about a character from

various backgrounds and lifestyle choices?

Religion is still a major part of many, many children’s

lives, but you wouldn’t know it if you took a look at children’s books coming

out today. I’m not asking for

books where religion is the sole theme of the story, although that would be

interesting, but at least some characters that have religious mindsets and that

acknowledge that, yes in fact, religion is part of culture, and part of the

lives of children and young adult readers.

Again, if I'm wrong about this, please leave me any examples or comments or thoughts below! I'm genuinely very curious :)

Friday, April 12, 2013

Another Guest Post over at "Kid Lit at UF"

Just wanted to let you know that I have another guest post up on the Kid Lit at UF blog! It's titled "Our Feral Child Obsession" and explores our enduring fascination with stories about the feral child, and what it means that they happen so often within the context of children’s literature. I trace the theme in art and history and then move into a few contemporary children's books (The Incorrigible Children and The Graveyard Book) Hope you enjoy!! And I'd love to hear others thoughts on this too :)

Here's the link:

http://ufkidlit.wordpress.com/2013/04/05/our-feral-child-obsession/

And here's a quick taste from the beginning of the post:

"What is a feral child? The dictionary defines this as a child who is in a wild state, especially after escape from captivity or domestication. Now while there are unfortunate real life examples of children who have been believed to exhibit feral qualities as we discussed in class, I will not be going into that here. Instead I’d like to ask the question, why have we as humans had such a cultural, and ultimately literary obsession, with the idea of the feral child?

If you really think about it, this fantastical idea of the feral child goes back many centuries, with one of the earliest examples being the legend of twin babies Romulus and Remus...."

Enjoy!

Wednesday, April 10, 2013

Real and Imagined Spaces: The Role of Ekphrasis in The Secret Garden

This semester has been crazy, as evidenced by my lack of blogging activity.... But I'm really excited to share this post with you, it's something I wrote for my Golden Age class. We have a class blog, and this is my final post, and the topic is one that I've been wanting to write about for almost three years!! Back when I was still majoring in art history, and trying to integrate my interest in children's books, I went through this time where I kept coming up with thesis ideas, and I started a running list of about 15 or so paper ideas, and this was my favorite, looking at the role of ekphrasis (which I'll define below) in The Secret Garden (and also in Jane Eyre, although I won't delve into that in this post). Hope you enjoy this post!!

~:~

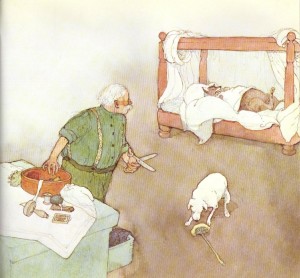

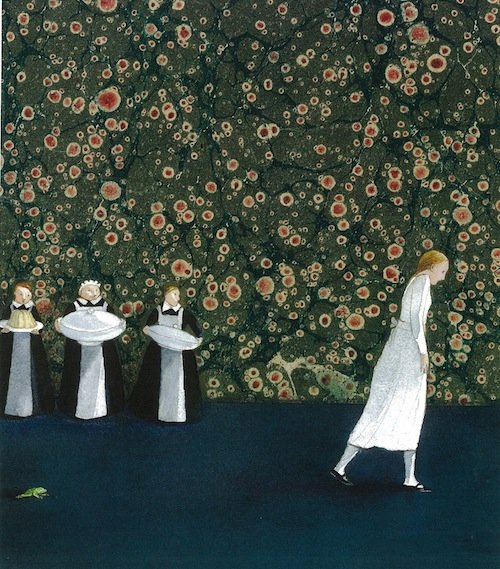

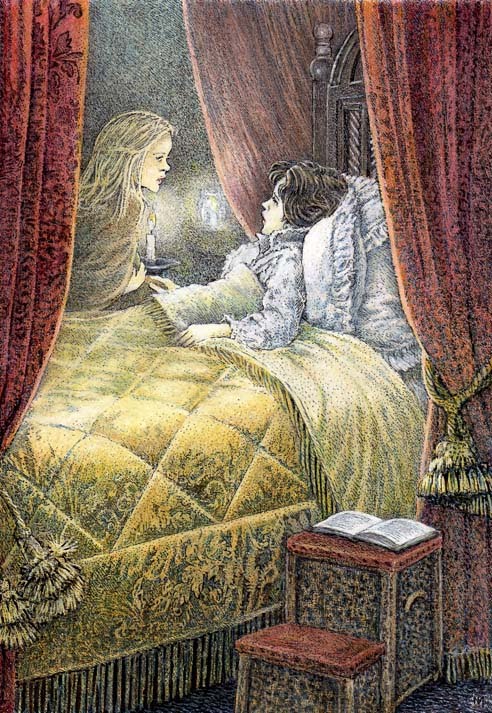

I read The Secret Garden for the first time two years ago, once on my own and then again shortly after with my little brother. I had seen the film when I was little but had never read the actual book. During the summer that I first read the book, I had just finished reading Jane Eyre and I could not help but see the many parallels between the two texts. However, perhaps surprisingly, the one that stood out the most was the integral role that art and illustration play in both stories. And not specifically physical illustrations on the pages, like the ones I've included hear by Inga Moore, but instead works of art and illustration that are describes via words throughout the novels. This literary tool, usually used to describe a work of art or illustration with words, is known as ekphrasis coming from the Greek word meaning "description". Moreover, ekphrasis is, according to the Penguin Dictionary of Literary Terms and Literary Theory, an "intense pictorial description of an object...a virtuosic description of physical reality in order to evoke an image in the mind's eye as intense as if the described object were actually before the reader" (252).

Thus in The Secret Garden, art and illustration play an important role in determining the real and imagined spaces that the characters, especially Mary and Colin, inhabit. In a way, the descriptions and importance of paintings, mostly portraits, and illustrations work in a similar vein to windows and doors, as thresholds for the characters to go between. As I read the text again for this class, I started paying more pointed attention to wear ekphrasis surfaces and kept a running list. I'll be giving some of these examples throughout this post, so let's look at what role this actually plays; why is it important? For both Mary and Colin, painted, imagined spaces serve as a form of reality for them. Colin for example has never really left his room. His windows are shut, and he has no access to the outside world, to "reality". Instead, he contents himself, or at least survives, by pouring over illustrated picture books, in which perhaps he imagines himself living out the fictional escapades of heroes within or at least taking strolls through beautiful landscapes. He also has the portrait, often covered up, of his mother when she was a child. She serves as his constant "human" companion, with his nurse and maid coming in and out every once in a while. Emphasizing the fact that Colin often lives in an imaginative world, is his first encounter with Mary in which he has a hard time believing that she is even real: " 'Who are you?,' he said...'Are you a ghost?...You are real aren't you?...I have such real dreams very often. You might be one of them.' (74). So for Colin, the imagined,dreamlike, painted space is his reality.

Dickon, on the other hand, is the complete opposite. He is always out in the open, always out in the real world. We can infer that he has little contact with paintings or illustrated texts. However his imagination thrives off of reality. In his wanderings through the real world out on the moors, instead of a dark, gloomy, stuffy room, he takes on a sort of mystical nature. He talks with the animals, he plays a pipe, and has a magical quality. So unlike Colin who has to use his imagination to create his reality, Dickon uses his reality to form his imagination. And where does Mary stand in all of this? Mary seems to be the fusion of both worlds, of an imagined reality and a reality fed by imagination. When she first comes to Misselthwaite Manor, Mary has interesting and somewhat intimate and gloomy encounters with the portraits around the house. For example when Mary first enters the home, Burnett provides us with this description: "The entrance door... opened into an enormous hall, which was so dimly lighted that the faces in the portraits on the wall and the figures in the suits of armor made Mary feel that she did not want to look at them. As she stood on the stone floor she looked a very small, odd little black figure, and she felt as small and lost and odd as she looked" (15). Right away, we get a sense that Mary has some sort of strange relation with the works of art in this home, they are given an animation, a real life like quality, as if the faces in the portraits are real people, looking at and judging Mary. These gloomy, old portraits seem to follow Mary everywhere, and as readers we get the sense that these portraits take on a realistic, human nature, they aren't just paintings they are these characters that fill the house. Another important moment is the description of Mary wandering through the house passing "hundreds of rooms with closed doors" (33) that goes as follows: "There were doors and doors and there were pictures on the walls. Sometimes they were pictures of dark, curious landscapes, but oftenest they were portraits of men and women in queer, grand costumes made of satin and velvet...She [Mary] walked slowly down this place and stared at the faces which also seemed to stare at her. She felt as if they were wondering what a little girl from India was doing in their house....she always stopped to look at the children... There was a stiff, plain little girl rather like herself...'Where do you live now?' said Mary aloud to her. 'I wish you were here'" (33). Thus, this moment may be the clearest one, where we witness Mary using these portraits as a reality to live in, she's staring at them and they stare at her, she even tries to hold a conversation with one. Thus this mirrors Colin's attempts to use his imagination to create a reality.

However, as time passes, Mary starts to open up to the "real world" outside the walls of the manor. She gets glimpses of it at first through the windows, which serve in a way to almost make illustrations or framed paintings out of the real world, since when she's behind the window she's not actually outside. And much in the same way as Dickon, who seems to fuel his reality with imagination and whimsy, Mary starts to do the same. For the first time she starts to form relationships with real people and in real spaces, not painted ones. However, even when it comes to her garden, it is described in a very artistic and story like way, as "some fairy place" (53), "a world of her own" (47), it's almost like the garden, is a painting or illustration that has finally come to life. Interestingly enough, when Mary encounters Colin they have many interactions over illustrated picture books and they share a connection through their use of their imaginations to create reality. And when Mary begins to describe the garden to Colin, before she reveals that's she's actually been in it, she is indeed painting a picture for him of the garden, a picture of words, almost like doubly layered ekphrasis (this scene is on page 79).

While there are many other examples, especially a really interesting one on page 159 with Dickon's mother in which she's described as "rather like a softly colored illustration in one of Colin's books" emphasizing this interplay of painted and real, I'll stop there as it's getting a bit long now, but this topic is just a fascinating one for me. The way that reality and imagination, real and painted spaces all mingle with each other in the characters of Mary, Colin and Dickon. As a final note, the specific illustrations I've chosen from Inga Moore's illustrated edition of The Secret Garden, all incorporate paintings or illustrations within the illustration which makes me thing that Moore picked up on this theme and may have delighted in creating these pictures within pictures.

|

| While this last image does not employ the picture within a picture theme, I've included because it a frame where we see all three characters, Mary, Colin, and Dickon, as they are abound to cross the threshold into the secret garden. Here we see the interaction of all three of these characters, and the interplay between reality and imagination |

~:~

And once this semester is done, I have some posts I've been wanting to write up, especially one about the afternoon I spent when Peter Sis came to campus and spoke with a small group of us and also gave a larger lecture, it was AWESOME, to say the least! So within the next month or so I'll have some new posts up and also will be having a guest post up around the end of May over at the newish and wonderful illustration blog, Pen & Oink, which you should check out if you haven't!! Here's the link: http://penandoink.com/

Tuesday, March 12, 2013

Guest Post over at UF KidLit

I have a guest post up on the "Kid Lit at UF" blog! It's titled:

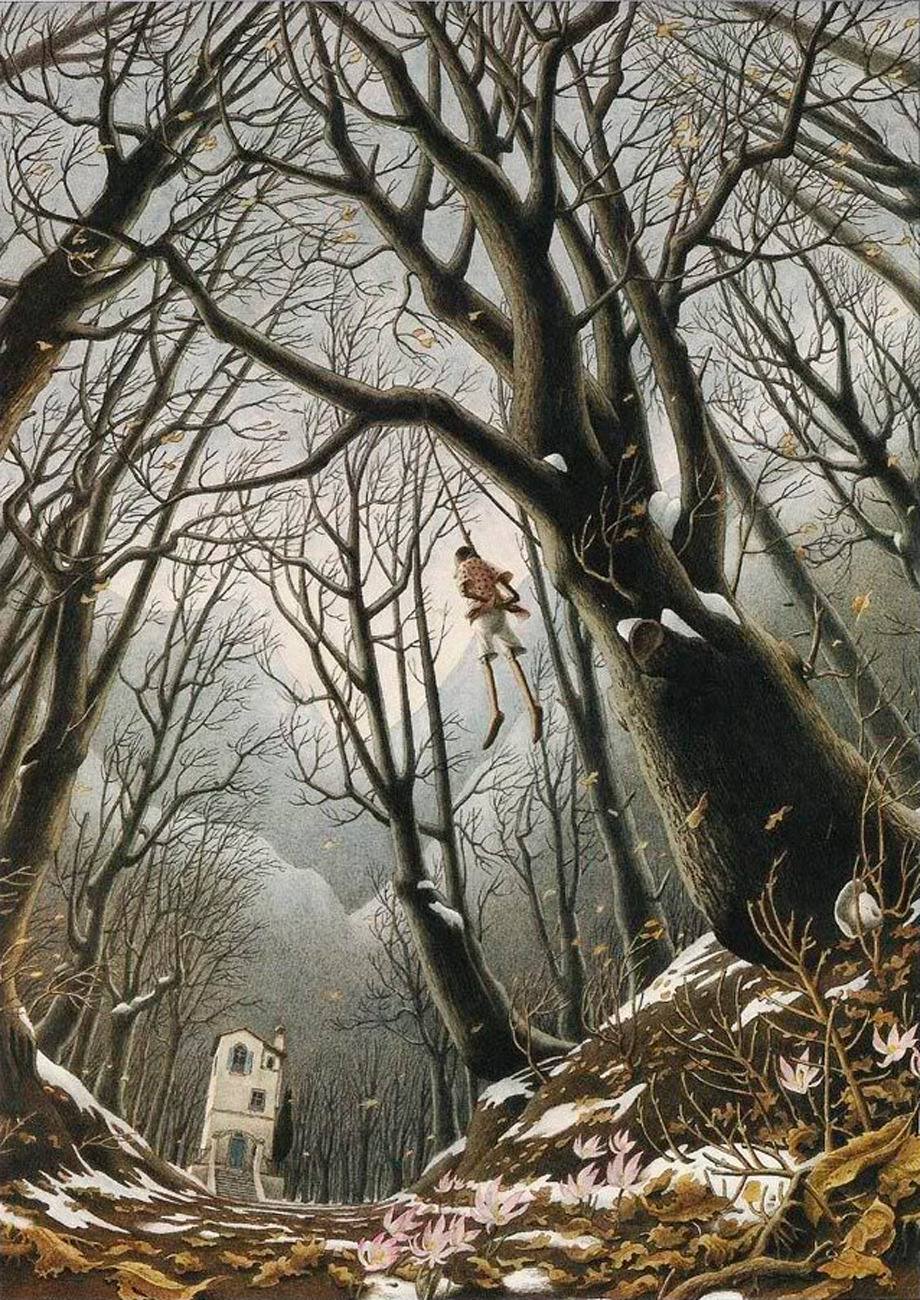

I was really excited because I found some fantastic illustrations that I hadn't seen before for this novel by Roberto Innocenti! I'll give you a sneak peak at one, but you'll have to click on the link and head on over to Kid Lit at UF to see more :)

http://ufkidlit.wordpress.com/2013/03/01/to-be-a-puppet-or-not-to-be-a-puppet-that-is-the-question/

To Be a Puppet or Not to Be a Puppet…That is the Question

In it I'm taking a close look at Carlo Collodi's Pinocchio , exploring the nature of "puppethood" and what it means for Pinocchio to be transformed and what difference it makes to be a puppet or a real boy.I was really excited because I found some fantastic illustrations that I hadn't seen before for this novel by Roberto Innocenti! I'll give you a sneak peak at one, but you'll have to click on the link and head on over to Kid Lit at UF to see more :)

Ok, fine I'll give you two!

Ok, now head on over to "Kid Lit at UF", they have some really great posts up:

http://ufkidlit.wordpress.com/2013/03/01/to-be-a-puppet-or-not-to-be-a-puppet-that-is-the-question/

Monday, February 4, 2013

Teasing out the "Beautiful" and the "Ugly" in Fairy Tales and Victorian Literature

What is beauty? What does it mean to be beautiful? In today’s world, when we read about a beautiful daughter who was virtuous in a fairy tale we immediately assume, “Wow, what sexist, awful fairy tale and Victorian writers, just because she’s virtuous means she’s automatically the most ‘beautiful’ person on earth. And then of course since her sisters are mean and bad, they are called ‘ugly’. How ridiculous!” With this mindset then, we turn on virtue, we start criticizing it, we start speaking about it in negative ways, we start mocking it. But is there something more here? What did these authors and tales mean when they bestowed this pronouncement of beauty or ugliness?

- Is this a modern day version of MacDonald's "princess" theory?

First, for modern readers, what it comes down to is the fact that in our world we have reduced beauty to someone who is physically attractive, someone that looks like a model or actress. However beauty, like the word love, is a loaded word. Perhaps what the authors of fairy tales or Victorian writers like George MacDonald are asking us to think about is not the fact that virtues make a person “beautiful” in the way we think of beauty. Instead acting good, being virtuous, actually having morals, makes a person beautiful. And it is not a surface beauty, it is a radiance that comes out, it is a joy, it is something intangible and almost imperceptible but we know it’s there. So although the media and even illustrators choose to portray the “beautiful princess” as the perfectly shaped and attractive girl, I do not think that these authors were working at such a shallow and surface level. George MacDonald, as a Christian, would have most likely been well versed in Christian thoughts on beauty. He surely would have been very aware of this passage from scripture, in Paul’s letter to the Philippians, that says:

Thus, with this in mind, MacDonald and others in his line of thought (ie Lewis and Tolkien), are not concerned with superficial beauty; they believed in ideals of the True, the Good, and the Beautiful and that bringing these things into your life and focusing on them could actually make a difference in your life. That what could happen is if one thinks on what is True, they’ll become a person who is true; if they think on Beauty, they’ll become beautiful; and if they think on the Good, then they will become the man or women that they are meant to become.

|

| Curious to read this and see how it fits in with my propositions in this post... |

And what of the mean, evil, ugly characters?? In the same way that we’ve reduced the term beautiful to attractive, we’ve reduced ugly to physically unattractive. However, I don’t know about you, but I haven’t seen many descriptions of the physical ugliness of let’s say mean sisters in fairy tales. It is an ugliness that exudes from inside, that taints their being, that mars the way we think of them. Granted sometimes like in George MacDonald’s The Princess and the Goblin, the goblins are actually physically ugly to represent their bad behavior, but I mean they are goblins, right?! This calls to mind a scene from C.S. Lewis’s first Narnia book, The Magician’s Nephew, in which Jadis, the witch, comes to life inside of the great hall. The children notice that as they move down the table there is slowly an almost imperceptible change that has come over all of these rulers, and the corruption that they practiced has trickled into their physical appearance (which we should note, could actually happen, trials and hardships, or joys and blessings, have a way of making themselves physically evident in our countenance). However, the queen, Jadis, is physically beautiful, but her greed, her evilness is evident to the children, and to them she becomes ugly, but no so much on the surface but a burning from the inside. In this way there is an illumination of the danger in correlating ugliness with physical unattractiveness.

- Recently this idea of the utterly beautiful but evil woman has probably been depicted best by Charlize Theron in "Snow White and the Huntsman"

Friday, January 25, 2013

The most important thing we've learned... Morals that SHOCK!

- Didactic literature in human form...AH!

Looking beyond power dynamics and the intricacies of academic dialogue on the nature of didacticism in children’s books, it is necessary to remember that all works of literature, for any age, are acting on some level as teaching tools. This teaching need not be heavy handed, with harsh morals and punishments like that found in evangelical texts for children from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. However, lessons are always being passed along through literature. Even as adults we are still learning through fiction, even if it is packaged through the pleasure of the aesthetic presentation, we are still being exposed to different perspectives and broadening our understanding of who we are as individuals and of the world we view through the lens of the novel; with every page we are learning how to be people.

.jpg)

With this in mind, it is essential then that stories for children actually teach them something. However, this teaching does not need to be conventional. It does not need to be didactic and saccharine, in fact if it is, it will fail as a book. Children are indeed some of the toughest and honest critics and to use Deborah Stevenson’s term, a book that fails to entertain, that fails to draw in its readers will not be honored with the “children’s imprimatur” (Stevenson 118). Humphrey Carpenter lays out this idea of the entertainment/morality balance in his essay, between the child’s desire for “adventure and imagination” and the adult’s desire for “moral examples” (Carpenter 1).

However in reading this essay, a statement that followed soon after this balance discussion caught me off guard. Carpenter goes on to say that in order for a text to be successful it must indeed fulfill these two desires, however he says that every once in a while a book comes along which achieves success despite failing to satisfy both parties. He gives Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory as his example stating that is “has been loved by children and hated by adults because it is full of fun and virtually amoral” (Carpenter 1). Was I the only one that found this strange? It was even stranger that Carpenter failed to give any support for his statement, leaving it merely as a given that everyone finds Dahl’s novel “amoral”. The first thing that came to mind was, I don’t know of any other book that has so many lessons and morals, some even explicitly spelled out, but in a way that is hilarious and entertaining. Dahl creates the ideal model for children to follow in the character of Charlie, and he then has four characters that exhibit extremes of what children should not be like. One of the most memorable excerpts from the novel is the Oompa-Loompa song directed at parents (if you'd like to hear it sung and watch it performed, it's actually included in the Tim Burton film, check it out here):

"The most important thing we've learned,

So far as children are concerned,

Is never, NEVER, NEVER let

Them near your television set --

Or better still, just don't install

The idiotic thing at all…

did you ever stop to think,

To wonder just exactly what

This does to your beloved tot?

IT ROTS THE SENSE IN THE HEAD!

IT KILLS IMAGINATION DEAD!

IT CLOGS AND CLUTTERS UP THE MIND!

IT MAKES A CHILD SO DULL AND BLIND

HE CAN NO LONGER UNDERSTAND

A FANTASY, A FAIRYLAND!

HIS BRAIN BECOMES AS SOFT AS CHEESE!

HIS POWERS OF THINKING RUST AND FREEZE!

HE CANNOT THINK -- HE ONLY SEES!

What used the darling ones to do?

Have you forgotten? Don't you know?

We'll say it very loud and slow:

THEY ... USED ... TO ... READ! They'd READ and READ,

AND READ and READ, and then proceed

To READ some more. Great Scott! Gadzooks!"

As I continued to think about Dahl’s novel and it’s relation to didacticism/morality and entertainment, I realized in a way, Dahl is doing for children’s books what Flannery O’Connor did for her adult readers. They both utilize the shock factor, they stay clear of heavy-handed didacticism. But they are in no way elevating or suggesting that readers should follow in the footsteps of the many amoral characters that populate the pages of their stories. Instead, they both utilize the grotesque in order to shock their readers and bring a realization of how they as people should act. Moreover the grotesque in a way brings on a sort of grace and salvation. And in Dahl’s case this produced not only for his readers, but also for the amoral children in his story because although they are cruelly punished, they do not perish, they come out alive, but severely altered, ready to start out on a better and more enlightened path, a path which we as readers are able to take without having to actually learn it the hard way.

Works Consulted:

Humphrey Carpenter’s “Secret Gardens”

Deborah Stevenson’s “Classics and Canons”

Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory

Jon M. Sweeney's article from American Magazine, “Grace and Grotestque” (http://americamagazine.org/issue/701/ideas/grace-and-grotesque

Wednesday, January 23, 2013

Final Installment of Only in a Fairy Tale

Only in a Fairy

Tale:

Discerning the Form

through the Art of Illustration

Part 5

“Physicalization

of Emotion”

In part 4 it was put

forth that fairy tales are filled with violence and brutality. But why the violence and physical

pain? What is the point? Is it bad

for children to be exposed to this?

Bruno Bettelheim once said that “Since ancient times, the

near-impenetrable forest in which we get lost has symbolized the dark, hidden,

near-impenetrable world of our unconscious.” Thus, many have agreed with Bettelheim that fairy tales are

ripe with desires and dreams and are a world where psychological traumas take

center stage. But what does this

have to do with violence, especially since our psychology is so internal rather

than external?

Adam

Gidwitz, author of A Tale Dark and Grimm,

explains this perplexity with the phrase “turning tears into blood”. In The

Seven Ravens illustration, Rackham gives viewers the exact moment where the

sister has almost made it to her brothers, but she has come face to face with a

locked door to which she has lost the key. Her solution is not to go back or to ask for help, she

literally cuts off her finger and this magically serves as a key to open the

door. Thus, all the love she holds

for her brothers, her fears and hopes coalesce in this painful sacrifice to

save her brothers. Gidwitz thus

claims that scenes like this take place because, “forests are where our fears

turn into wolves, our desires into candy houses…where the emotional problems we

face…are physicalized, externalized, and ultimately conquered. Where tears are

transformed into blood.” Thus, fairy tales and their illustrations, take all of

these unknown, confusing, uncomfortable and abstract feelings and transform

them into terms children know all to well, physical pain. And they slowly realize that if cuts

and bruises eventually heal, then perhaps their emotional trauma will one day

heal too.

To see more of Adam's thoughts on fairy tales check out his post here and his website: http://www.adamgidwitz.com/

Hope you enjoyed this five part series on fairy tales!!

Saturday, January 19, 2013

Part 4 of Only in a Fairy Tale

Only in a Fairy

Tale:

Discerning the Form

through the Art of Illustration

Part 4

Reality

of the Brutality

Fairy tales,

especially from the Brothers Grimm, have some surprisingly violent moments and

perhaps even more interesting is the almost blasé way that these moments are

related, meaning that these moments are not really dwelled upon or emotionalized,

they simply are. These include

everything from The Juniper Tree,

where a young boy is murdered by his mother and feasted upon by his father to

the abducting and massacring of maidens in Fitcher’s

Bird and the more well known wolf surgery scene in Red Riding Hood. More

than most versions of Red Riding Hood,

Zwerger’s illustrations emphasize the surgical procedure that is about to

happen. While we as readers must

suspend our disbelief in coming to terms with the fact that Red and her

Grandmother are still alive after being devoured by the wolf, there is nothing

magical in the practicality of exhuming them from within the wolf. The woodcutter takes on the role of

doctor in Zwerger’s scene.

Moreover, Zwerger does not shy away from actually showing us, in the

moment, what it would have looked like to see Grandmother coming out of the incised

belly of the wolf, perhaps all that is missing is some blood, or maybe the

woodcutter is just that talented.

Friday, January 18, 2013

Part 3 of Only in a Fairy Tale

Only in a Fairy

Tale:

Discerning the Form

through the Art of Illustration

Part 3

Flatness

of Fairy Tales

In the minds of many today, fairy tales are

usually dictated by the Disney versions, the color palette and specific idea of

whom each of the character are.

For many, Cinderella is not just any girl, it is Disney’s girl, and the

same goes for many of the other fairy tales colonized by Disney. However, in

A.S. Byatt’s introduction to Maria Tatar’s annotated Grimm, she states that the

original tales have a “discrete, salutary flatness” and that they are “older,

simpler and deeper than the individual imagination.” I started to realize that

these tales are truly flat, but not in a negative sense. They are flat in that they are

universal, timeless, and they are able to connect to any individual, regardless

of who they are. They do not need

to be specific and elaborate, they instead have the ability to reach out and

touch the human soul and illuminate truth in a way that lights up the

imagination and creates this magical space where the reader or listener is

hooked and floods the page with the colors of their own imagination.

Byatt also

cites Max Luthi’s description of fairy tales: “an abstract world, full of discrete,

interchangeable people, objects, and incidents, all of which are isolated and

are nevertheless interconnected, in a kind of web…” Thus from one tale to the next, princesses and princes,

wicked step-mothers and kings, fill the role of their archetypes, but are not

unique individuals, and could easily be transplanted between tales. Moreover,

the aesthetic of the tales, the colors and imagery, has a certain palette,

Luthi says: “red, white, black and the metallic colors of gold and silver and

steel.” This bareness even in

terms of color is then typified and exalted by the illustrations of Lisbeth

Zwerger. Here in a faultless

flatness she exudes the tension, annoyance, fear, movement, and pulse that

fills The Frog Prince. Zwerger is

able to wedge her illustrations into the flatness of the fairy tale, her

princess could be any girl, what is unique are the emotions she elicits, even

in its bareness and simplicity, and the magical space that she creates between word,

book, image and reader.

Also, check out Donna's wonderful review of a new Lisbeth Zwerger collection over at "32 Pages"! : http://32pages.ca/2012/11/14/lisbeth-zwerger-and-the-brothers-grimm/

Monday, January 14, 2013

Part 2, Only in a Fairy Tale

Only in a Fairy Tale:

Discerning the Form through the Art of Illustration

Part 2

“Eucatastrophe”: Sudden and Miraculous Grace

Almost

anything can happen in a fairy tale.

Main characters are murdered, blinded and banished. Characters often start out weak, and

must venture through an unknown forest, facing their fears and battling

enemies. And when all hope seems lost, some miracle takes place and the main

character comes out on top and all is well in the kingdom again leading to their

“happily ever after”. Some may

complain that this is not realistic, but that is the point, fairy tales are not

supposed to be about our reality, they live in their own reality and play by

different rules. Moreover, this

form of story gives its readers hope, that as difficult and seemingly

impossible the world may seem, the fairy tale always gets you out of it and

your problems are resolved.

J.R.R.Tolkien

has probably described this literary phenomenon the best. He refers to this fairy tale happy

ending propensity as “eucatastrophe”.

He coined this term from Greek: ευ-

"good" and καταστροφή "destruction". In his essay “On Fairy-Stories”,

Tolkien states:

“The consolation of fairy-stories, the joy of the happy ending… or more

correctly of the good catastrophe, the sudden joyous “turn”: this joy, which is

one of the things which fairy-stories can produce supremely well, is not

essentially 'escapist', nor 'fugitive'. In its fairy-tale—or

otherworld—setting, it is a sudden and miraculous grace: never to be counted on

to recur. It does not deny the existence of dyscatastrophe, of sorrow and failure: the possibility of

these is necessary to the joy of deliverance; it denies (in the face of much

evidence, if you will) universal final defeat…”

In his illustration for Rapunzel, Zelinsky gives us the moment

following the eucatastrophe. Readers

have just finished witnessing the almost religious miracle that changes the

lives of Rapunzel and her beloved, the healing power of her tears to cure his

blindness. Playing into this religiosity, Zelinsky ends his tale with this icon

or Renaissance-style religious composition, showing that all is well, their

happy ending is real, and Rapunzel, like the grace-giving Virgin herself, is

the deliverer and stands at the center of their family’s world.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)